Conservatism: A Rediscovery

Review of the 2022 book 'Conservatism: A Rediscovery' by Yoram Hazony

Written by Elias Priestly, you can find all his previous articles on the Australian Natives Association website and find more of his content on 𝕏 @Aussie_EliasP

For those who have been paying attention, the National Conservatism movement appears to be the rising newcomer on the block of mainstream conservatism.

J.D. Vance, picked by Trump as his VP in his run for president, recently sparked some outrage from liberals when he denied that America is a propositional nation at the 2024 National Conservatism conference. Certainly, in today’s day and age this is a statement of political heresy and signals a turn away from the current establishment conservative position. For this reason, among others, it’s important to look at Yoram Hazony’s relatively recent book, Conservatism: A Rediscovery, which contains the ideas behind this apparent challenge, and examine how Western nationalists should see this new movement.

Before jumping into reviewing the book, it is worth briefly establishing who Hazony is. Yoram Hazony is an American-born Jewish nationalist philosopher, president of the pro-Zionist Herzl Institute in Jerusalem, and chairman of the Edmund Burke Foundation. National Conservatism is a project of this second group. The book Conservatism: A Rediscovery also comes after two other controversial books by Hazony, The Virtue of Nationalism (2018) and A Jewish State: Herzl and the Promise of Nationalism (2020).

It is the second book that is largely illustrative of Hazony’s concerns. Hazony is worried that Jews in Israel are embracing liberalism and “woke” ideology and are rapidly losing the conservative ideological foundation and resources to maintain a religious nationalist Zionist state in Israel. He believes that familiarity with the great tradition of Anglo-American conservatism may serve as an antidote to the corrosive influence of liberalism and Marxism on Jewish and, more broadly, Western society. For this reason, it’s worth remembering that this book is not necessarily for the benefit of only his Gentile readers, but is also for a Jewish audience. But with all of that out of the way, let’s jump into the review.

Conservatism is split into four sections, the first relating the history of Burkean conservatism which is taken as the paradigm for national conservatism, the second discussing the underlying philosophical principles of the conservative movement, the third looking at current affairs, and the last being comprised of an autobiographical chapter that seeks to draw “notes on the conservative life” from Hazony’s own personal experiences. Overall, the narrative of the book is a great conflict between the political empiricism of conservatism and the political rationalism of liberalism and Marxism, which, while a little simplistic, serves reasonably well as an underlying narrative for the political stance Hazony advocates.

Section One: The Conservative Tradition

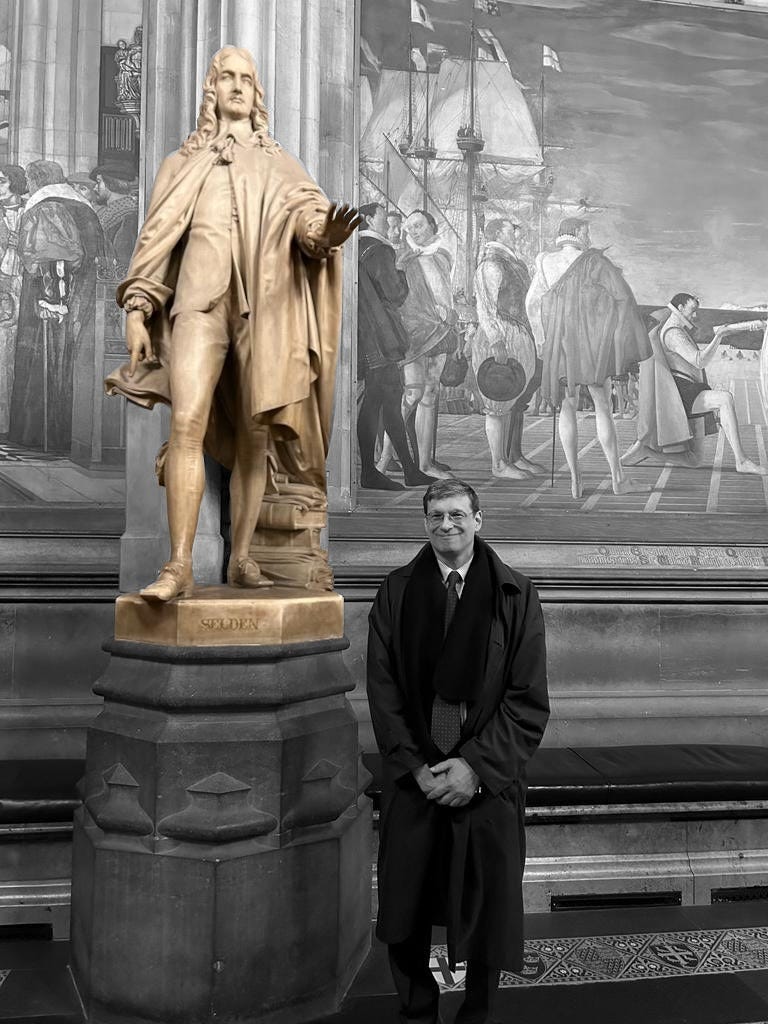

The first section of the book begins with an interesting chapter rehearsing the Anglo-American conservative tradition. Beginning with John Fortescue, Hazony goes through the political thought of a number of more obscure pre-Burkean conservatives including Richard Hooker and John Seldon. Seldon’s defense of natural law provides Hazony with an opportunity to celebrate the seven Noahide laws of the Talmud as “the most reliable” interpretation of natural law (p.17). Perhaps he’d be less willing to celebrate Seldon’s belief that Jews had been involved in ritual murder of Gentiles. Putting this aside, however, this reliance on a rather thin albeit Biblically grounded set of laws as the best exemplification of natural law means that Hazony’s conservative tradition sits on a somewhat fragile foundation. This section of the book felt strange to me when I read it, and upon further examination this is probably because it is one point where Hazony’s underlying project of reorienting political thought “away from Hellenistic and Roman influences” in favour of Judaic influences clearly shines through. As long as the reader keeps this agenda in mind, however, there is much to be gained from this chapter.

The other noticeable aspect of the first chapter was the way that Hazony expunges the High Tory position from his conservative tradition and constantly champions Protestant and parliamentarian views. Despite opening the first chapter with the statement that “a conservative is a traditionist,” it is still important to ask who makes it into this version of tradition and who doesn’t. A traditionalist conservative will certainly show much more sympathy to the tradition championed by King James I and Robert Filmer than Hazony does when he celebrates the Glorious Revolution for its “restoration of a Protestant monarch” (p.20).

On the whole, though, the chapter on the history of English conservatism introduced me to much that I was unfamiliar with, and is a valuable read for anyone who is not already conversant with the Burkean tradition. Burke himself is the culmination of the English conservative tradition here, and from this tradition Hazony derives five main principles as the foundation of the conservative state: historical empiricism, nationalism, religion, limited executive power, and individual freedoms. He also provides a good critique of Locke and his liberal approach to political philosophy, which, unlike conservative empiricism, rests upon axioms supposedly derived from “reason” but actually lacking any evidential foundation.

The second chapter continues on with the history of the conservative tradition by shifting to an overview of American conservatism. In this chapter Hazony traces how the five principles of conservatism shaped the American constitution through the efforts of the Federalists. Jefferson is the great villain of this chapter as the revolutionary apostle of liberalism in America, a supporter of liberal internationalist adventures in his support for revolutionary France, and an opportunistic immigration supporter. Hazony takes great delight in recounting how the support new immigrants provided for Jefforson’s agrarian ideals led him to backflip from his previous immigration restrictionist views.

In this chapter Hazony dismisses the notion of America as a creedal nation in favour of a more typical nationalism based on ancestry, language, etc. However, by throwing emphasis on the non-Anglo background of John Jay, who Hazony points out was a descendant of “French Huguenot and Dutch immigrants” (p.45), he begins to construct his assimilationist account of civic nationalism. Of course, it is entirely true that Jay was not an Anglo-American, but there is no discussion in the book of the possible racial limits of assimilationism. Later on in the chapter, Hazony continues this line of thinking by claiming that the denial of citizenship for blacks in the Dred Scott case of 1857 undermined “the idea of a single American nation.” This again displays a certain ambiguity and equivocation in Hazony's “nationalism.” Sometimes shared ancestry seems to matter, at other times it is a civic construct that can be adopted by multiple races in a single society. I doubt Hazony had Israel in mind in the case of the latter.

Some of the better points of the chapter are the stress on the importance of unitary executive with the American president based on the British monarchy (pp.54-55) and Hazony’s discussion of Hamiltonian protectionism and industrial espionage, used to develop the US into an industrial superpower by stealing innovations from Europe and developing American industry through the use of tariffs. Hazony will use this later on in his discussion of modern China as a state that has been able to develop itself at the expense of the United States through its own use of the same policies.

On the whole, this chapter is somewhat less relevant to Australians but still interesting for its exploration of the independent development of another British colonial society from English roots. Nonetheless, there is still a need to focus on our own unique national conservative tradition as it departs from Britain and this is something that Hazony generally mentions throughout the book as he sees national conservatism as a project that can be realised in varying forms across the world. Part of the role of the Australian Natives’ Association in Australian politics must be to raise more awareness of our own historical empirical experience and tradition as captured in the works of some of our great writers such as Banjo Paterson and Charles Pearson, among many others.

Section Two: Philosophy

The third chapter begins the second section of the book which focuses on philosophy, with Hazony laying out the theoretical concepts behind his paradigm of conservatism. This chapter discusses staple traditionalist points such as the importance of nation, family, honour, hierarchy, and loyalty. Indeed, “mutual loyalty” is particularly important for Hazony because it functions as a substitute for kinship in his project of building a civic account of nationalism and the family in conservatism. Again, this chapter features much Jerusalem and little Athens - Tertullian would be pleased. Hazony introduces the notion of giving kavod, the Hebrew word for glory, to one’s parents as per the Biblical commandment and explains that this word is cognate to kaved, meaning heavy or weighty (p.119). From this moment on, we are bombarded with references to this through the importance of “giving weight” in our eyes to various important persons and institutions that conservatives typically admire. An at times wholesome implementation of an interesting idea, but it is also wearing after a while and typifies Hazony’s need to shoehorn in Judaic concepts to play a role in the European tradition.

Hazony’s discussion of philosophy is centred primarily in his critique of the liberal paradigm of political science for its ahistorical rationalism. Hazony wants political theory to develop by induction after the model of Newton's Principia in contrast to the axiomatic rationalist approach of Cartesianism. Hazony boils this down to three elements of determining the verisimilitude of a scheme, which are that a truer scheme reveals more causes and effects, explains them more precisely, and uses fewer concepts. This is the weakest element of the entire book and, in general, the key crippling weakness of the entire nationalist conservative paradigm. Hazony makes a good case that rationalist thought alone can come to almost any conclusion, and thus that the liberal “truths of reason” that are supposedly apparent to all are merely an alternative tradition to conservatism, one with much less empirical support and testing. His empiricism, however, is equally weak to anyone who is even slightly versed in philosophy and basic problems in epistemology. This is one point where the Traditionalist or Platonist can point out that reason is also important, so long as it is in the service of supra-rational principles.

Hazony heads in the right direction when he cites Seldon’s critique of liberal rationalism as reserving “nothing for divine authority” and insists on the need for tradition (p.172). If tradition is read with a capital-T, then many in nationalist politics would agree. However, Hazony again goes too far in his rejection of rational thought simply on the grounds that when not constrained by tradition it can lead to “Marxism or to a quasi-Darwinian racial politics as easily as it does to liberalism” (p.172). Mere human traditions are equally as relativistic, and there is no strong reason provided by Hazony for favouring the Burkean tradition over other plausible options. This section is also where white identitarians, relegated to an endnote where they can be hidden, are also accused of being rationalists who replace Holy Scripture with the exegesis of racial science by disinterested reason. Hazony simply ignores the possibility that they may be right, and this reveals the relativist streak that is inevitable upon a rejection of reason. This weakness of national conservatism is apparent next to more appealing conservative projects, such as the Hegelian project of synthesising in a Christian matrix the rationalism of the Enlightenment with the organic traditionalism of the ancient polis.

Moving beyond this weakness of the book, there are again plenty of good points in this chapter. Hazony’s stress on nation, family, and constraints upon liberty leads to a strong critique of liberal individualism and self-interest, and he laments how liberalism has led to the breakdown of the family and the proliferation of pornography, LGBTQ+, easy divorce, and abortion. He also comments on how fertility has crashed to below replacement rates and non-assimilated immigrants are seen as equal to members of the nation based on the liberal lens of seeing each person as an abstract individual apart from their collective identities. I also appreciated how he pointed out that the liberal theory of consent removes obligations while keeping rights - a very destructive development.

Hazony’s basic solution to all this is adopting empiricism, turning back to the conservative tradition, and rebuilding “clans” or associations, with the basic example of a clan being a religious community. This continues his civic nationalism with its mutual loyalty. He even does the meme by pointing to the “mixed origins” of the French and English in various English tribes as the paradigm for his mutual loyalty model (p.115).

In the fourth chapter, he focuses on God, Scripture, family, and the congregation. He suggests that morality needs to be based on the one standard set by the God of Hebrew Scripture and for people to do “what is right in the eyes of God” rather than “what is right in the eyes of man.” Hazony is correct, but again, he seeks to ground us primarily in the Jewish tradition when Plato also famously said, against Protagoras, that God, and not man, is the measure of all things.

This chapter featured one of my favourite parts of the book where Hazony contrasted the real traditional family with the nuclear family and pointed out that the nuclear family had shaped the built environment of suburbia. The final chapter of section two stresses the need to focus on the “common good” as the basis of government policies and to consider collective entities as themselves real and not just the constituent atoms that make them up. A key point here is that the state cannot be neutral on religion and religion is needed to maintain a cohesive public square. On the whole, the second section of the book featured some key weaknesses within what was a competent discussion of key conceptual pillars of the conservative tradition.

You have just read part one of this book review by Elias Priestly, part two will be released Friday morning. Subscribe to have it sent straight to your inbox!