Percy Grainger: A Composer of the Australian Ingvaeonic

In search of an Australian nativist art form

Written by Elias Priestly, you can find all his previous articles on the Australian Natives Association website and find more of his content on 𝕏@Aussie_EliasP

Two things occurred recently that have prompted me to write an article on one of Australia’s great native-born composers - Percy Grainger. Firstly, I happened to start really getting into listening to his music again; and secondly, a prominent Australian National Socialist, Thomas Sewell, announced his interest in establishing a nationalist art movement which he calls the “Ingvaeonic.” There is a fortuitous coincidence to these two occurrences, because I believe that Grainger’s ideals for Australian music and Sewell’s conception of the Ingvaeonic share many points in common. In this article I first lay out my understanding of the Ingvaeonic and then explain why I believe that Grainger’s work could be seen as an early Australian contribution to this concept.

In a recent stream, Sewell described the need to create an art movement that would balance traditionalism and futurism while expressing the unique racial characteristics of the Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian branches of the white race. This new movement would then act as the aesthetic embodiment of the political ideals of nationalists in Australia and form the style for the branding of a nationalist political party. The name chosen for this movement is “Ingvaeonic,” which is a name for the subgroup of West German languages that includes Old Frisian, Old Saxon, Old English, and their descendant language forms. By naming the movement “Ingvaeonic,” the idea seems to be to understand language in the broad sense as the totality of the cultural expression of a particular racial type, one that Sewell believes to include Australians as a descendent Anglo-Saxon population. While I have personally expressed my disagreement with elements of the politics that Sewell embraces and the specific nuances of his interpretation of Australians as a people, the idea of the Ingvaeonic is still very interesting and worth pursuing as one possibility for the expression of Australian art. In fact, I believe that this idea was already touched upon in the musical compositions and philosophy of Percy Grainger.

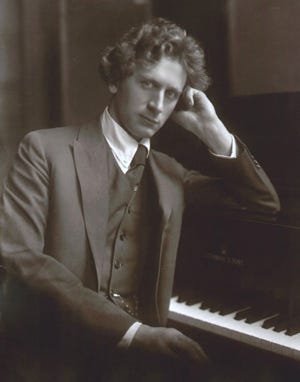

Percy Grainger was born on the 8th of July 1882 in Brighton, Melbourne. As his father was a drunk and womaniser, and Percy was bullied in the few years he attended school, he ended up being mostly raised and educated by his mother, Rose, whom he later would characterise as a thoroughly Nietzschean woman. Importantly, Rose taught him music and also exposed him to Nordic culture by teaching him from texts such as the Saga of Grettir the Strong, an ancient Icelandic text. Retrospectively, Percy would characterise that saga as “the strongest single artistic influence on my life.” Grainger was in Australia until the age of thirteen, and being already incredibly talented as a pianist, he was then sent overseas to further his study of music at the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt, although he later claimed he learned little there compared to his formative experiences in Australia. Nonetheless, he did come to a realisation at the Hoch Conservatory that he has recorded in his introduction to the Aims of his autobiographical museum:

While studying music at the Hoch Conservatorium in Frankfurt from 1895 to 1899 I was struck by the fact that the most gifted composition students were all from the English-speaking and Scandinavian countries. I foresaw that a period of English-speaking and Scandinavian leadership in musical originality and experimentation lay just ahead - a florescence comparable to the iconoclastic innovations of the Worcester composers of the 13th century, of Dunstable of the 15th century, of the pre-Bach English string fancies of the 17th century.

Grainger’s belief in an Anglo-Nordic renaissance, a seed planted by his mother’s teachings, had already taken root and begun to develop. It would be fertilised by a deeper exposure to the English folk tradition.

Today, Grainger is best remembered for his role in the first English Folk Song Revival at the turn of the 20th century and his compositional work in arranging folk songs into intricate band settings. One such work, often considered to be one of his masterpieces, is “Lincolnshire Posy,” which displays his desire to be faithful to the authentic style of the folk performances which he spent much time collecting, studying, and recording. Nonetheless, while this piece is certainly wonderful to listen to and establishes Grainger in the tradition of those nationalist composers who drew inspiration for their art music from the material provided by their folk, I would not say that “Lincolnshire Posy” is an example of Ingvaeonic art. It expresses the English folk tradition in a sophisticated form, but it does not have enough of the pan-Germanic character and hard edge required by a truly Ingvaeonic piece.

Percy Grainger - Lincolnshire Posy

In order to understand the qualities that should prevail in a particularly Australian Ingvaeonic music, at least if one agrees with Grainger’s assessments of a future Anglo-Nordic musical culture, it is time at last to turn to Grainger’s “Hill Song No.1” and his own commentary on it in the essay Percy Aldridge Grainger’s Remarks About His Hill Song No.1.

Percy Grainger - Hill Song No. 1 (1902/1921)

“Hill Song No.1” is a complex polyphonic and harmonically dense piece of music in a grand style. Here, the hard edge that “Lincolnshire Posy” lacks is consciously present. As Grainger writes in his Remarks:

I consider Hill-song No. 1 by far the best of my compositions. But the difficulties of conducting its highly irregular rhythms are almost prohibitive. At the time of composing Hill Song No. 1 (1901-02, aged 19-20) wildness and fierceness were the qualities in life and nature that I prized most and wished to express in music. These elements were paramount in my favourite literature – The Icelandic Sagas.

However, the composition is not merely Scandinavian in temper, but is thoroughly Australian with Grainger stating that its musical idiom was developed out of “certain nationalistic attitudes that were natural to me as an Australian.” Grainger believed that Australia was fundamentally based on an “island” geography and mentality that was close to the Nordic mentality in its focus on seafaring, exploration, and overseas settlement. We may recall here that Australia’s first industry was sealing and whaling, with the rough pioneer sailors sleeping on the small islands of the stormy Bass Strait. While Australians often turn to the land-mentality of the Outback and the Bush for our understanding of our character, Grainger provides us with an interesting counterpoint in his view of Australian character in its relationship to the ancient Nordic type.

Returning to his remarks on the Hill Song, Grainger states that along with wide tone scales and irregular rhythms, which he saw as characteristic of Nordic folk music, he thought that the extreme polyphony of the piece was essential to its Australian character. As he writes,

“My Australian ideal [was] of a many voiced texture in which all, or most of the tone-strands (voices, parts) enjoy an equality of prominence and importance…”.

This equality of many voices expresses the egalitarian character of the Australian that many would think of when they consider our national character. Finally, a reasonable amount of discord in the dense harmonic writing helps to give his piece its sense of strength, power, and seriousness without devolving into the worst excesses of the modern and postmodern movements in art music.

Turning to one last key example of his music, Grainger also wrote a “Jungle Book Cycle” based on his love for Kipling’s work and particularly his character of Mowgli in the Jungle Book. While this is not one of my favourites from Grainger’s body of work, it is a good example of his interest in the primal strength of barbarism as opposed to the decadent modern form of civilisation. Kipling’s famous “wild boy” character exemplified this theme of man at his strongest when raised in the brutal world of the jungle. This combined his with his conscious racialism to form the idea of a Nordic revolt in art against the modern “civilised” world. The same concept finds excellent expression in a passage from the first section of the second half of Labour writer William Lane’s great Australian novel, The Workingman’s Paradise:

Oh, for the days when our race was young, when its women slew themselves rather than be shamed rid, when its men, trampling a rotten empire down, feared neither God nor man and held each other brothers and hated, each one, the tyrant as the common foe of all! Better the days when from the forests and the steppes our forefathers burst, half-naked and free, communists and conquerors, a fierce avalanche of daring men and lusty women who beat and battered Rome down like Odin’s hammer that they were! Alas for the heathen virtues and wild pagan fury for freedom and for the passion and purity that Frega taught to the daughters of the barbarian! And alas, for the sword that swung then, unscabbarded, by each man’s side and for the knee that never bent to any and for the fearless eyes that watched unblenched while the gods lamed each other with their lightnings in the thunder-shaken storm!

While I am a Christian man and am not particularly enamoured by pagan doctrines and gods, I can, like Tolkien, appreciate the unique character of Northern Courage that still forms part of the spirit of our branch of the Anglo-Nordic race in Australia and clearly manifested itself in the actions of the ANZACs at Gallipoli and in the charge of the 4th Light Horse Brigade at Beersheba.

Lastly, lest I seem to overstate Grainger’s racialism and Nordicism, it is worth noting that he felt that music was a universal language and that each racial type had its own contribution to make to music. He was happy to let the African express himself as an African and the Asian to express himself as an Asian. Once more, to quote him from his Aims:

It would seem only natural for Australia to become a centre for the study of musics of the islands adjacent to Australia - Indonesia no less than the South Seas. Some of the world's most exquisite music is found in this area.

Yet none of these exotic musics, however charmful, should draw Australian musicians away from intense participation in the all-important developments of experimental music in the white man's world. The vistas opened up by the innovations of Beethoven, Wagner, Grieg, Alois Haba, Cyril Scott, Scriabin, Arnold Schoenberg, Arthur Fickenscher and others, should be explored. It would be a wonderful thing if Australia should be the first country to live to the axiom: "Music is a universal language".

Percy Grainger, like many artists, was a flawed man with complicated relationships and strange personal proclivities. Nonetheless, one relationship that is to be much admired is his lifelong loyalty to his native country - our own beautiful land of Australia with its still hidden depths and secrets that await expression in the full power of a future art latent in the soul of our folk. I will leave the reader with one final example of what I see as Grainger’s contribution to the Australian Ingvaeonic - “Colonial Song.” May it inspire artists to consider the native Australian character when creating their own nationalist Ingvaeonic art.

Percy Grainger - Colonial Song (1912/1918)