The Making of a Catholic President, Kennedy vs. Nixon

A review of Shaun A. Casey's book from the archives of the original National Observer

Article written by prolific writer, editor, organist and composer Dr Robert J. Stove in 2010. Read the article as it was originally published here. Shared with permission from the author.

"I gave them [political enemies] a sword, and they stuck it in and they twisted it with relish. And I guess if I had been in their position, I’d have done the same thing." — Richard Nixon to Sir David Frost, 1977.

It is to the United States’ eternal credit that a high American civilisation survived Woodrow Wilson’s crackpot foreign policy. It is, if anything, still more to the United States’ credit that a high American civilisation survived twelve years of Franklin Roosevelt. (The more archival evidence about FDR emerges, the more misguided appears every recent attempt to whitewash his sycophancy to Stalin, and the more apt for his state becomes the Earl of Essex’s verdict on Elizabeth I: "as crooked in [his] mind as in [his] carcase".) But it is not at all self-evident that a high American civilisation can survive John F. Kennedy’s enthronement, the fiftieth anniversary of which comes on apace. To JFK, Sir Christopher Wren’s epitaph still applies: "If you seek his monument, look around."

All America’s current discontents, even when not directly caused by Kennedy’s reign — Supreme Court Justice Earl Warren, leading judicial activist, got his start under Eisenhower — were aggravated by it. Contemplating Camelot evokes Churchill’s famous words: "The terrible Ifs accumulate." Without JFK, there would have been no Lee Harvey Oswald. Without Oswald, no Lyndon Johnson. Without Johnson, no Great Society (and hence no black underclass whose activism culminated in Hurricane Katrina’s televised bacchanal). Without the Great Society, no draft-dodging student proletariat. Without the draft-dodging student proletariat, no left-wing Democratic insurgency in 1968. Without the left-wing Democratic insurgency in 1968, no right-wing challenge by Alabama’s George Wallace, and therefore no wafer-thin popular majority for Richard Nixon. Without the wafer-thin popular majority for Nixon, no presidential paranoia about retaining office; therefore, no Watergate. Without Watergate, no Indo-Chinese collapse. Without Indo-Chinese collapse, no neocon revanchisme. Without neocon revanchisme, no Obama. Further: without JFK, no Senate career for Ted Kennedy, whose full support for abortion and for unrestricted Third World immigration compounded the malice of his academic fraud and lethal Chappaquiddick deceit. Macaulay’s estimation of a French revolutionary demagogue suits the oleaginous Ted to perfection: "In him the qualities which are the proper objects of hatred, and the qualities which are the proper objects of contempt, preserve an exquisite and absolute harmony."

So in truth, post-Kennedy America’s cultural battleground validates the repulsive yet clever Brecht’s aphorism: "You may not be interested in war, but war is interested in you." Could JFK’s 1960 victory have been prevented? If so, when? Which groups supported him and which opposed him?

Shaun A. Casey — of Washington DC’s Wesley Theological Seminary — emphasises that aspect of Kennedy’s campaign which generated most coverage at the time, but has been most comprehensively forgotten since: Kennedy’s (notional) religious allegiance. Census Bureau director Richard Scammon remarked, shortly after Oswald struck, that Kennedy would "be remembered for just one thing: he was the first Roman Catholic elected President. Period." American politics in 1960 remained haunted by what Casey calls "the ghost of Al Smith": that is, of the New York Governor who in 1928 was the first Catholic ever to seek the presidency. Smith’s Catholicism did him more harm than good, and (the Quaker) Herbert Hoover thumped him at the polls. After 1928, it became American political orthodoxy that no Catholic could be President. Still, JFK boasted benefits that the hapless Smith lacked. He had personal charisma, a billionaire father, a glamorous spouse, an Ivy League background, a much-publicised war record, and a Senate tenure during which he had made few if any outright foes.

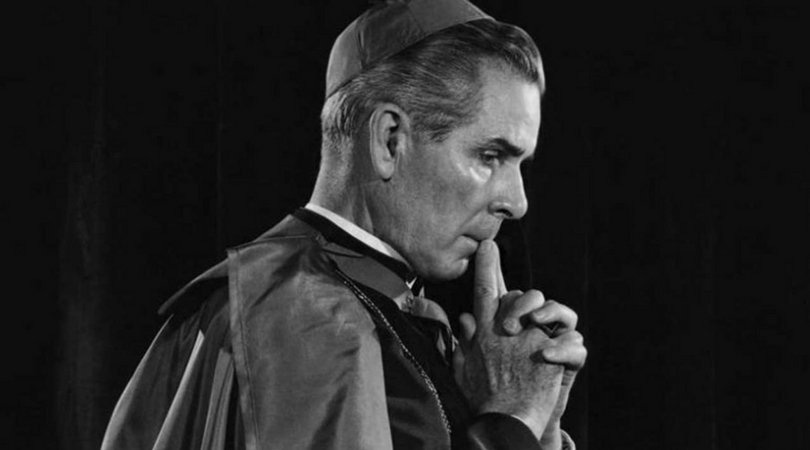

With the 1956 contest to become Adlai Stevenson’s running-mate, Kennedy had achieved the best possible outcome: securing national celebrity, while avoiding the blame that would have attached to him if he had been on the Democratic ticket that year. Few Democrats relished, in 1960, the prospect of Stevenson leading them to a third consecutive defeat. Kennedy therefore looked like potential Oval Office material. As for American Catholicism in general, it attained during the 1940s — and kept until Vatican II — an unprecedented cultural confidence. According to a 2002 biography of eminent theologian Fulton Sheen: "Some nine million people subscribed to 333 [American] Catholic newspapers in 1942. ... Catholics reported about 86,000 converts annually." Evelyn Waugh wrote with atypical optimism, in 1949, of "the American epoch in the Catholic Church".

Notwithstanding this, even Kennedy’s warmest admirers generally doubted that his Catholicism would be actually advantageous. Casey stresses something little discussed in previous JFK literature: the great personal fear of Protestants which Kennedy admitted to his intimates. In 1960 much of America remained segregated religiously, no less than ethnically. Protestants and Catholics led largely separate social lives, and intermarried far more seldom in the USA than in, say, Australia. The Ku Klux Klan, having sunk from its 1920s apex, revived in the 1950s. Rare, by 1960, were the Southern politicians who dared resist a leading Klansman to his face, or rather, to his hood.

At least Ku Kluxers avoided the responsibilities of cognitive stature. More subtle and equally obstreperous was the Protestant intellectual establishment of 1960, for which Kennedy’s presidential hopes meant a flagrant attack on the so-called "separation of church and state". Never mind that the US Constitution’s First Amendment, ostensibly guaranteeing this separation, guarantees no such thing. Never mind that outside America, Protestantism usually scorned church-state rifts (as the histories of Edinburgh, Geneva and Pretoria show). Never mind that Jefferson — usually credited with demanding "a wall of [church-state] separation" — was no Christian at all, but a crypto-Jacobin, Bible-doctoring Deist. Jefferson’s views have no more relevance to any Christian nation’s beliefs than do those of the nearest imam, bonze or lama (who, unlike Jefferson, does not claim Christological expertise). These uncomfortable data mattered nought. JFK called himself a Catholic; Catholics owed their first allegiance to a foreign power; ergo, JFK owed his first allegiance to a foreign power. On this syllogistic theme, America’s Protestant press devised seemingly inexhaustible variations, many of which displayed an obsessive terror that Kennedy, if elected, would prohibit contraceptives. (The press either did not know or did not care that every Protestant church in the world prohibited contraceptives until 1930.)

No Protestant spokesman questioned the syllogism’s first premise: whether Kennedy had any right to call himself a Catholic, given how he thought and acted. Of course, as we now realise, JFK took Catholicism’s dictates no more seriously than he took Shintoism’s or Zoroastrianism’s. This situation never occurred to Protestant leaders even as a conjecture. Oddly enough, atheist Jewish leaders must have suspected something of the reality; otherwise their enthusiasm for JFK becomes inexplicable. Kennedy, who received 81 per cent of the Catholic vote, received an astounding 83 per cent of the Jewish vote. How? Anti-Catholicism was — and is — in many atheist Jews’ DNA, a truth readily observable from Sidney Hook’s condemnation of Catholicism as "the oldest and greatest totalitarian movement in history". A genuine Catholic might well have exacerbated Jewish voters’ bitter remembrance of Father Charles Coughlin’s pre-war zenith. Quite apart from Coughlin’s Judaeophobic outbursts, Hook and his fellow pragmatist philosophers could not pardon sincere Catholics for having had the tasteless audacity to clobber Spanish Reds in 1939. Nor could comparably influential Protestants. Judging by the repeated protests (which Casey cites) against Franco’s occasional harassment of Jehovah’s Witnesses, a foreign observer might have assumed that Spain’s ruler had been nominated as Democratic candidate. But whereas a genuine Catholic had no chance of winning over atheist Jews, a fake Catholic ... ah, now you’re talking.

Several Kennedy aides thought that if JFK ignored the religious issue, it would go away. JFK, to do him justice, knew better than that. Nixon — who had one prominent Catholic confidant, Father John Cronin — would doubtless have preferred to leave religion aside; but Casey demonstrates how vulnerable the Republican campaign was to Klan and, more often, quasi-Klan intrigue. Kennedy, fortified by his own considerable gift for rhetorical charm, decided on taking the battle into his opponents’ camp. This he did, most famously in his September 1960 speech (written by his Unitarian friend Ted Sorensen) to assembled Protestant ministers in Houston. He said, inter alia:

“I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute, where no Catholic prelate would tell the president (should he be Catholic) how to act ... where no church or church school is granted any public funds or political preference ... I believe in an America ... where no public official either requests or accepts instructions on public policy from the Pope. ... I do not speak for my church on public matters — and the church does not speak for me.”

At the time, Catholics and Protestants united to hail this credo as a marvel of democratic statesmanship. Read afresh in the cold light of post-Christianity, it can be recognised as marking the first fatal exhibit of that complete religious privatisation with which the West must now live, and which reduces religion to a mere Sunday morning hobby, of no more social import than hunting butterflies or collecting bottle-tops.

No-one, Nixon arguably excepted, emerges well from Casey’s account. Numerous leading Protestant clergymen proved (until JFK propitiated them) ignorant and bigoted; numerous leading Catholic clergymen panicky and disingenuous. The latter could well have said, in effect, "Yes, we’re Catholics, and we have voting rights. You got a problem with that?". Instead they made the mistake against which Waugh cautioned them: "Many American prelates speak as though they believed that representative, majority government were of divine institution." Because Protestants could always play better majoritarian cards than Catholics could do — why would they not, since they did form a majority? — they could set the terms of debate.

We know the outcome of polling day. Nixon’s support from most Protestants, from most of the South and Midwest (though not Texas, New Mexico or Missouri), from newspaper owners (though not journalists), from Hawaiians (after a recount in that state), and from most radio listeners (to whom his rich baritonal speaking voice in debates sounded much more impressive than Kennedy’s surfer-boy squawk), could not quite get him across the line. Kennedy won not solely the Catholic and Jewish votes but the liberal vote, the Eastern vote, the journalists’ vote, the TV watchers’ vote, and Texas, this last partly because of LBJ’s long-standing electoral appeal among dead people. More crucially still, Kennedy won the Illinois vote — let’s hear it for Chicago Mayor Richard Daley — and the Chicago Mafia vote. Mafioso Sam Giancana, hardly likely to be erroneous on the subject, later told a Kennedy mistress: "Listen, honey, if it wasn’t for me your boyfriend wouldn’t even be in the White House."

Initially Nixon intended to launch a formal court challenge to the result. Had he been able to obtain Eisenhower’s support for this plan, it is hard to determine how he could have failed. Given the older man’s continued personal prestige, even those who would cheerfully have insulted Nixon would not have dared to impugn Ike. But even here Nixon proved unlucky. Already Eisenhower had undercut Nixon’s confidence by saying (when asked by reporters for an instance of Nixon’s achievements as Vice-President), "If you give me a week, I might think of one." Ike could no more be relied on for moral support after the election, when he told Nixon that he would oppose any idea of a challenge.

Nixon continued to seethe. At a private function during December 1960, he announced: "We won, but they stole it from us." Few shared his concern. Merchants of Western media globaloney — forever willing to abuse Salazar, Verwoerd, Ian Smith, Chiang Kai-Shek, and Ngo Dinh Diem for imperfect ballot-box representation of the General Will — developed, when it came to regretting America’s Great Filched Election of 1960, an abrupt and profound autism. As future Vietnam general William Westmoreland would scrupulously explain to Time magazine’s readers in 1982: "Without censorship things can get terribly confusing in the public mind."

Kennedy’s subsequent career is beyond Casey’s brief, and has already been analysed in gruesome detail by earlier biographers. Suffice it to say here that JFK’s devastating illness (Addison’s Disease), his dependence on powerful and befuddling medicaments for managing this illness, his continued erotic irresponsibility, his betrayal of Diem (on which even hitherto loyal Catholic supporters had choked), and the increasingly frequent public accusations of a previous secret wife: these things ensured that if he had survived 1963, his rule would almost indubitably have ended in 1964, either by natural death or by disgrace.

In any event, the villains and the victims long ago passed away. Meanwhile America’s Catholic episcopate made with Kennedyism a Faustian bargain which it has yet to live down. (A stinging post-election epigram by Episcopalian columnist Murray Kempton alluded to JFK’s religious hypocrisy: "We have again been cheated of the prospect of a Catholic President.") Obama in 2008 scored not only most of the black vote, but — despite, or maybe because of, his loathing for unborn children — three-fifths of the total Catholic vote. At least growing numbers of vocal American Catholic layfolk appreciate that an existential threat to them is being carried out from above, and that from the typical bishop they need expect no help whatsoever. The average British or Australian lay Catholic, by contrast, perceives no governmental endangerment to his faith that cannot be averted by truckling unto Caesar, by alcoholic binges, by emasculating the priesthood, and (best of all) by reading Lord of the Rings for the thirty-eighth time.