The Women Aren’t Having Babies

An analysis of the causes, effects and solutions of Australia's declining fertility rate

Written by Flynn Holman, find more of his content on 𝕏 @Flynn_Holman_

In recent years, Australia has been grappling with a stark decline in fertility rates, plunging to historic lows that threaten to reshape the country's economic landscape. According to data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), women are now expected to have only 1.6 babies over their fertile years, significantly below the replacement level of 2.1. This trend, which has persisted despite a brief uptick in 2021 likely due to pandemic-related lockdowns, signifies profound demographic shifts with far-reaching consequences for Australia's future.

Economic Impacts of Declining Fertility Rates

The declining fertility rate in Australia will have economic implications across the short, medium, and long term. Critically, this economic impact will disproportionately affect young people, the working population of Australia’s future. As the proportion of elderly Australians grows relative to the working-age population, the burden of supporting retirees through pension and healthcare schemes will intensify, leading to fiscal challenges for the government. As more and more resources are funnelled into public health and aged care, there will either be less money to spend on infrastructure, education and housing or otherwise there will be an increased tax burden on a smaller taxpaying cohort. Either situation leads to an inevitable decline in the living standards of the working-age population.

The impact of an aging population in the medium term is even more concerning, particularly with the prospect of demographic shifts compounding the secular stagnation of our economy. A shrinking pool of young workers will dampen Australia’s capacity for productivity, growth, and innovation. This pool of workers is traditionally more inclined towards entrepreneurship and technological advancement and the portending dearth of fresh ideas and risk-taking could stifle innovation, ultimately hampering Australia's competitiveness on the global stage.

Why are we here?

Australia's experience echoes broader trends observed in Western countries today and throughout history. Periods of low birth rates have most notably been triggered by unfavourable economic conditions and societal change, such as during the Great Depression in the 1930s, the post-war period in Eastern Europe and the ‘sexual revolution’ throughout the 1960s and 70s. Societal shifts, including delayed marriage, increased educational attainment, and economic hardship have contributed to the postponement of childbearing among young couples.

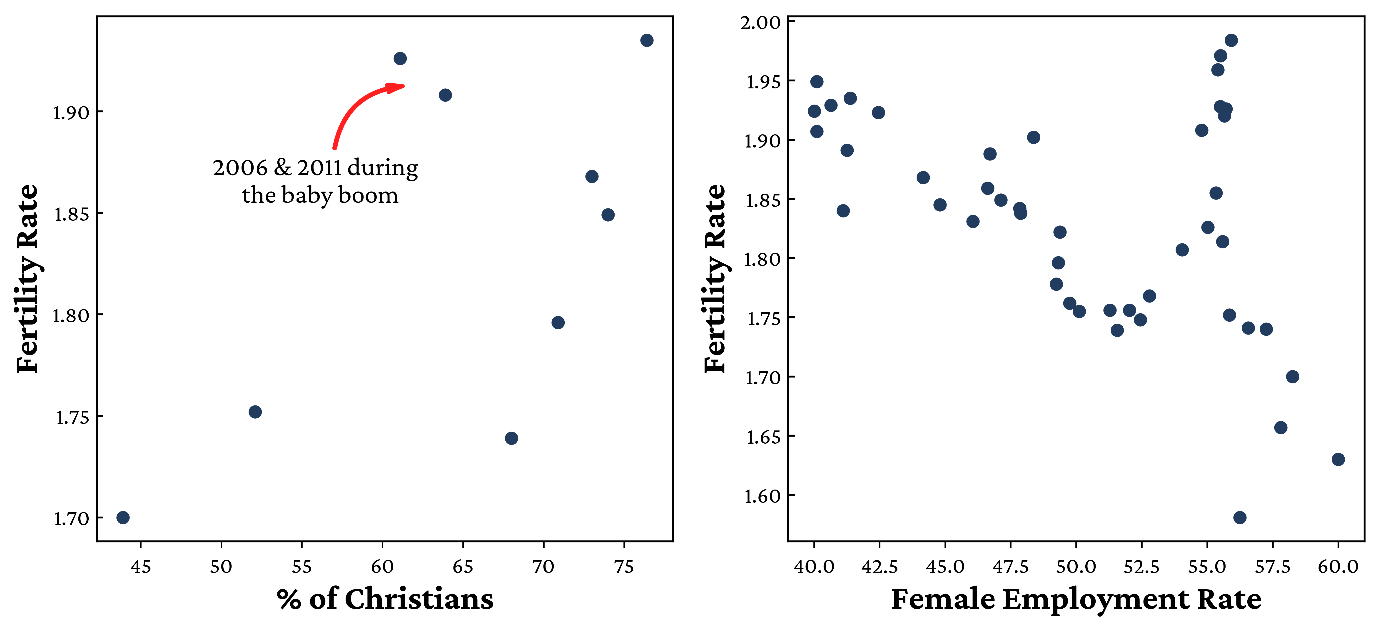

Several factors have underpinned Australia's declining fertility rate since the global financial crisis in 2008. Economic uncertainty, exacerbated by high housing prices and job instability has dissuaded many from starting families, and this only continues to worsen with the current housing and cost of living crisis. Shifting trends over recent years have seen women remove themselves from the home and enter the workforce in overwhelming numbers. The female employment rate has increased by 20 points since 1978, and this has been accompanied by a 20% decrease in the fertility rate of Australian women. Many women have favoured career development and personal aspirations over natural maternal instincts and most have chosen to postpone or forgo parenthood altogether.

Another cause of declining fertility rates is the increasing secularism of Australian society, with self-identifying Christians nearly halving in number over the last 45 years. It is well known that religious families have more children, with one Austrian study finding that practising Christian parents have twice as many children as secular parents. In particular, irreligious women today have increased access to contraception and abortion, which has played a role in their reduced childbearing.

Addressing the Challenge: What Can Be Done?

The conventional approach to ‘solving’ this issue is to import a mass number of young immigrants to artificially bolster Australia’s working-age population. This is a poor solution for several reasons.

Immigration is a purely short-term solution; it is well known that second-generation immigrants increase in wealth and education compared to their parents, thus mimicking the same causal factors of the current population’s lack of fertility. Whilst importing a working-age population may temporarily mitigate the impacts of a low fertility rate, ultimately the decline will continue. Not only is it only a short-term solution, but importing immigrants could actually have a net negative effect on the current population’s fertility rates. More immigrants into Australia means increased competition for the available housing stock, leading to a price spike, disproportionately affecting the prospective young families by increasing their financial burden and reducing their incentive and ability to raise large families. Moreover, the well-documented immigration fuelled crime creates dangerous communities no one would want to raise a family in, just another strong disincentive to raise children.

So clearly immigration is not the solution, but what is?

Policymakers need to explore targeted approaches to encourage native-born Australians to have more children. Restrictions to abortion access is a controversial method by which the fertility rate among the existing Australian population could be raised, a solution often ignored due to the political impracticality of implementation. The pro-life argument against abortion is a compelling one, murder of innocent life is never justified, by restricting this abhorrent practice which has taken root in most Western nations, the fertility rate problems in Australia could be swiftly addressed. Several historical cases show the impact of abortion laws on the birth rate. Take, for example, communist Romania during the 1960s and 70s — after a period of freely available abortion, abortions and contraceptives were severely restricted from 1966 to encourage population growth. One recent analysis showed that this policy decision saw an average increase in fertility rate of 0.5 babies per woman. A similar analysis of the effect of the Roe v Wade decision in the United States in 1973, concluded that the decriminalisation of abortion in America led to a 4% reduction in the national birth rate. Clearly restricting this practice will positively impact both the morality and economy of Australia.

Improving economic conditions and lifestyle affordability for young families is another important aspect of saving the Australian economy from disaster. Policy proposals such as financial subsidies for childcare, tax benefits for large families, and simplified adoption systems could all play a role in encouraging more couples to start families. Whilst it is hard for some to admit, we must recognise that the biological role of women is to birth and care for children. Encouraging female workforce participation has had a negative impact on fertility and coercive policies aimed at pushing more women into the workforce could exacerbate demographic challenges by further delaying childbearing, only compounding the problem.

Australia’s declining fertility rate presents a complex challenge with profound economic implications for Australia’s future. The growth of the retiree population presents a major burden for the coming working populace and invariably the political class will propose immigration as a solution. Not only will this have a negative effect on Australian society at large, it will undermine any real solutions to revert halt and reverse Australia’s crashing fertility rate.