Written by Elias Priestly, you can find all his previous articles on the Australian Natives Association website and more of his content on 𝕏 @Aussie_EliasP

Our survival depends upon a return to Tradition.

Anyone who has spent any time immersed in right-wing ideology and culture will undoubtedly have stumbled across the name of René Guénon and his “Traditionalism.” In the ivory towers of academia, which have declined into mere money-making schemes, the ideas of Traditionalism are seen as fanciful. Reputable conservatives will talk about Edmund Burke, and maybe even Thomas Carlyle, but Guénon and his followers would certainly be a step too far. Nevertheless, it is absolutely necessary that we, the traditionalist conservatives, ground ourselves in a serious study of Traditionalism and do not rely solely on a vague distaste for the modern and romanticism. Our survival depends upon it.

So, why is it necessary to have this approach of Traditionalism? Traditionalism is necessary because the starting point of a paradigm will govern and condition the entire system. Guénon’s approach was to begin with the ‘Absolute’ and to faithfully trace out the universal metaphysical principles that flowed from it before seeing how they could be applied to traditional forms of civilisation. As he famously said at the beginning of the second chapter of The Crisis of the Modern World,

“It is true that there have always been many and varied civilizations, each of which has developed in a manner natural to it and in conformity with the aptitudes of this or that people or race; but distinction does not mean opposition, and there can be equivalence of a sort between civilizations with very different forms, so long as they are all based on the same fundamental principles - of which they only represent applications varying in accordance with varied circumstances.” (p.21)

Without understanding these “fundamental principles,” traditional civilisation forms will be misunderstood, and we will remain stuck using modern political categories like “class” which are deviations from the true principles of caste or estate. A clear example is how much of what is called “conservatism” concerns itself only with the movement of degenerate digital money, which is a quantitative and virtual alienation of value from the sacred realities of things. In order to overcome modernity and become grounded in a real traditionalist conservative position, we must return to Tradition and its principles and categories of analysis, which requires us to take our own European Tradition of Christianity seriously.

This means we must look to Orthodox Christianity.

One of the most famous contemporary Christian Traditionalists, Alexander Dugin, has claimed that the Western Church, including both Roman Catholicism and its Protestant offshoots, in falling away from the Eastern Church lost its inner esoteric and metaphysical life and continued only as a rigid exoteric dogmatic structure without mystical content. The clearest indication that Dugin is correct in taking this stance is the confusion of Catholics and Protestants when faced with Orthodox epistemology. To their eyes, Orthodoxy appears to be an arbitrary and anti-intellectual doctrine divorced from a clear external foundation in the “plain meaning” of Scripture or the proclamations of an infallible (in “faith and morals”) Pope. Whether Orthodoxy is praised for its “anti-rationalism” or condemned for its “obscurantism” in neither case is it properly understood.

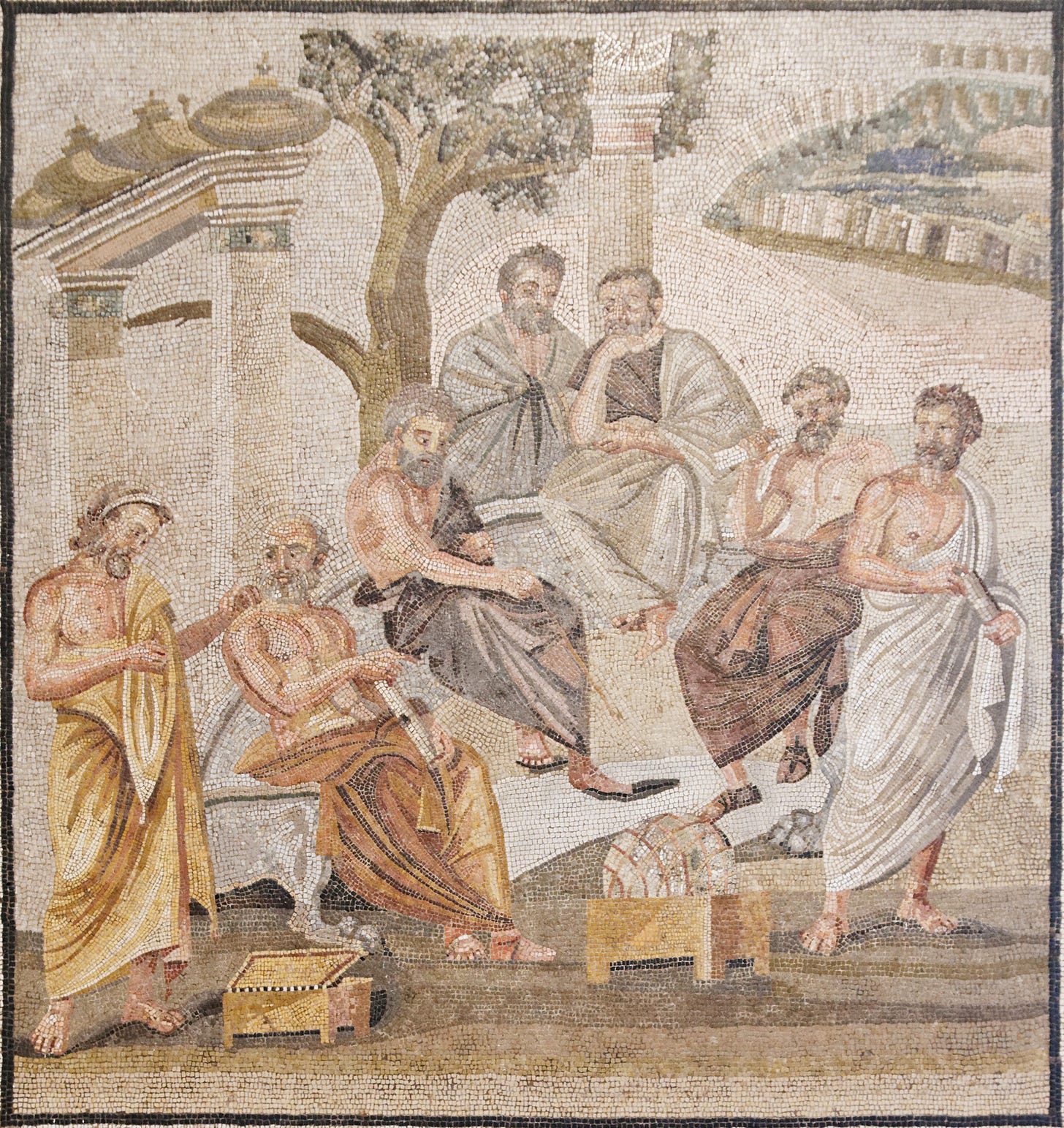

In actuality, this situation reveals that neither party even understands the traditional teaching about knowledge and its criteria in the Western Tradition. In Theaetetus 152C, Plato lays down the criteria of knowledge as (1) infallible cognition of (2) what is real. As Lloyd Gerson has pointed out many times, this rules out all empirical perception and discursive reasoning, or any other form of mediated thinking, as all such mediation implies a representational “gap” between subject and object that allows for the possibility of error. Knowledge, in the strict sense, must always be a self-reflexive intellectual intuition that is immediate - noesis. As Parmenides put it, “to think and to be is the same” and this is also what is meant by the famous Delphic maxim which instructs one to “know thyself.” All empirical and rational true opinions are thus simply images of non-representational knowledge and this knowledge requires self-transformation in order to be realised in an individual person. This is what is meant by theosis or deification in the Orthodox Church, and this is why it is so central to its teaching. Incidentally, this is also why the aside on theosis in Theaetetus 176A - 176C is not unrelated to the dialogue’s central topic of discovering what knowledge is, despite the confusion of most modern scholars.

All dogmas are externalisations of the content of theosis which is achieved through participation in Christ and His salvific work. The Church is silent on its mysteries not because it is “anti-rational” and obscurantist but simply because what is non-representational cannot be represented in image or speech but only made present in sacramental mysteries. The Church is “the pillar and ground of truth” (1 Timothy 3:15) not based on appeals to Scripture or the Pope but due to its identity as the body of Christ who is Himself the Truth, the identity of thinking and being as the one Logos who is the many logoi of creation.

Upon reaching this point, one may still wonder what all this has to do with the politics of conservative traditionalism in a more mundane sense. Even accepting that truth can ultimately only be grounded in the Holy Trinity, and thus the Orthodox Christian Church, this seems to be politically meaningless in a practical sense. Of course, as the Roman Empire declined in its decadence and was battered by waves of barbarian migrations and invasions, many people of the ancient world may have thought the same regarding this small, strange initiatory cult called Christianity. Nonetheless, it was Christianity, as Eusebius pointed out in his Life of Constantine, that eventually led to the inner revitalisation of the Empire.

Today, as we are again faced with civilisational decadence and waves of barbarian migrations, we must turn to the “pillar and ground of truth” as the foundation for the traditionalist conservative and Christian nationalist political program in Australia, for all else will fall and the wise man does not build his house upon the sand. The civilisational theosis of Political Platonism and the project of Platonic Futurism will fail without a core of Christian initiates who will guide the Australian people towards national repentance.

We cannot allow that to happen. Australia’s survival is unnegotiable.